Kilimanjaro is crowned with a crystalline carapace. At sunrise this gleams golden. Shaped like a Victorian plum pudding, the extinct volcano is a looming presence in the surrounding African savannah. Some mornings long ribbons of gauzy mist enshroud the base, on others it hides behind clusters of white and grey clouds. “The mountain is shy,” explains my Masai guide. The mountain is also endangered – its snowy crowning glory may soon be gone.

Hemmingway Legacy

When Hemmingway wrote The Snows of Kilimanjaro, in 1938, and described the ice-fields, it may not have occurred to him that 80 years on, the snows would be history. In fact, recent studies of the glacier and snow pack, measuring as far back as 11,700 years, concur the current situation is unique. There are satelite photographs from space, published by NASA, showing the shinking ice cap. A National Geographic video discusses the loss and causes. These include global warming, climate change and de-forestation of land around the base, now used for farming.

Queen Victoria’s Birthday Present

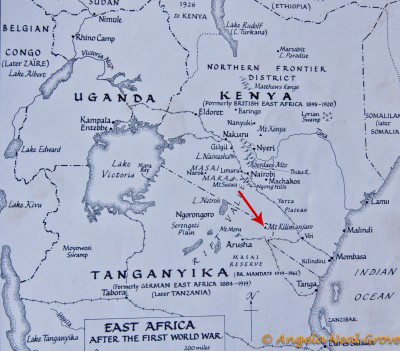

Kilimanjaro, which stands over 19,000 ft, straddles the border of Tanzania and Kenya. It is said to have been given to Kaiser Wilhelm by his doting grandmother, Queen Victoria. He had complained he did not have a volcano in his territories. She had some to spare in Uganda and Kenya. So, allegedly, he received Kilimanjaro as a birthday present from Her Majesty and the map was redrawn.

Today, those wishing to climb Kilimanjaro, must approach from Tanzania. The highest mountain in Africa, it attracts about about 10,000 climbers per year who take five or six days to reach the summit. Kenya, however, claims best photo opps, especially from Amboseli National Park.

Photographing Volcanic Amboseli

Amboseli is all about Kilimanjaro and its ashy volcanic legacy. The vast tracts of land with its fretwork of game trails are dusted salty white. In many places even termite mounds are white. Dust devils of ash errily dance over the horizon as the day heats up.The green reed-filled swamps where elephant and hippos wallow are fed by springs and run off from glaciers and snow melt. The swamps team with acquatic flora and fauna. The abundant herds of zebra, antelope and wildebeast are a few of the 50 resident mammals. There are also 400 species of birds. The water also supports much tree and bush life and the herds of goats and cattle which the Masai lead each day from the safety of their bomas. (Bomas are traditional Masai villages. Homes and compound for animals are surrounded by a thick predator-proof hedge made of thorn bushes).

Currently tourism is an important source of revenue and employment. From lodges such as Satao Elerai, hunters with long lenses in Land Rovers are out at daybreak as the mountain makes its daily debut and the daytime pagent begins with a chorus of crickets and bird calls. All that is left of the velvety star-studded blackness of the African night are lion, hyena and kudu prints in the dusty elephant paths.

What Does the Future Hold for Kilimanjaro?

In a dozen years the snow and glaciers maybe gone. Will there be alternative sources of water for people and animals? What might they be? I pondered this one morning recently. Kilimanjaro was the first thing I saw when I opened my tent flap. The remaining snowcap gleamed. In the distance a string of gray elephants plodded along age-old tracks fretting the ashy ground at the base of the volcano just as they have done for thousands of years. Do they sense what the future might be?

Safari to Kenya, September 2012. There are seven diary posts and a roundup on my Caves and Hills Travel Blog.

[…] This was Mount Kilimanjaro, with just a thin topping of snow, on my last visit to East Africa. The snows and glaciers which once topped the the mountain inspired Hemmingway’s book and subsequent movie The Snows of Kilimanjaro For a personal view and more read my post, The Snows of Kilimanjaro […]